Parasites of the Past - Changes in Anisakid burden in Puget Sound

In the Wood Lab, we are traveling back in time assessing how parasite assemblages have changed in fish hosts in the Puget Sound over the past century through the use of museum specimens from the Burke Museum. While this project encompasses many species of fish, I am specifically looking at carriers of Anisakis sp., which infects whales and dolphins. This project will shed light on how the risk of parasitism in marine mammals has changed in the Puget Sound and surrounding area.

Photo from the Burke Museum's Fish Collection.

Global Change in Anisakid Prevalence in Marine Mammal Prey

Using a dataset compiled by the Wood Lab of all publications on Anisakis sp. and Pseudoterranova sp. (a species of Anisakid that infect mainly seals and sea lions) prevalence in fish around the world, I am working to assess how global Anisakid burden has changed in prey species of endangered marine mammals. In effect, my research addresses if the risk of parasitism to marine mammals has changed on a global scale via the fish they eat. This work is nearly complete, so check in in the next few weeks for an update on my findings!

Change in Anisakid Abundance in Alaskan Salmon

In my newest project, co-led by Dr. Rachel Welicky, we are assessing how anisakid abundances have changed in commercially harvest Alaskan salmon using canned salmon collected from the 1970s to present. This is an effort to determine how parasite abundances have changed in resident killer whale diet species across the Gulf of Alaska. This study was made possible by, and is being conducted in close association with the Seafood Products Association, which has collected canned salmon for over 4 decades.

Assessing Parasite Prevalence in Killer Whales

There are four populations encompassing two ecotypes of killer whales in the Pacific Northwest. Some of these populations of killer whales are doing well, like the mammal-eating Biggs killer whales, while others are struggling, like the salmon-specialist Southern Resident. There are many factors influencing the decline in Southern residents, but the three most highlighted are a lack of prey, a a polluted habitat, and increased ocean noise (see the research conducted by Oceans Initiative the suite of lethal and sublethalfactors contributing to their decline). My research focuses on how parasites are impacting Southern residents: how infected are they, and are parasites influencing their overall health? Additionally, I am working to determine whether there are differences in how parasitized these other populations in the Pacific Northwest are in comparison to their endangered cousins. This is a work in progress in collaboration with Northwest Fisheries Science Center, the Wasser Lab at the University of Washington, Oceans Initiative, and Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

Photo by Toby Hall for Oceans Initiative

Parasites as an energy sink

Many marine mammals that have parasites can live seemingly healthy lives. When burdens get increasingly large, then parasites can cause major health problems like ulceration. However, just because a parasite is not causing direct health impacts doesn't mean that they are not having an effect. For example, if seal is not finding enough food, i.e. is nutritionally stressed, then parasites may play a bigger role in their health by taking up more energy than the seal host can spare to lose. I am working to quantify the energy lost to parasites in marine mammals by counting, weighing, and measuring all of the parasites found within the digestive tract of necropsied seals, sea lions, porpoises, and whales. This work will inform future studies on the implications of parasite infection in marine mammals.

Women in Marine Mammal Science

I have been a member of the Women in Marine Mammal Science (WIMMS) Initiative for the past two years. We are working to shed light on the unique struggles that tend to hold back women in this field of study. In 2017, we sent out a survey to our professional society asking about their views on what limits women in marine mammal science. This was followed by a workshop at the Society for Marine Mammalogy Conference in Halifax, Nova Scotia on October 28, 2017. We are currently analyzing the data resulting from the survey to quantify what major hurdles women face in this field. To learn more, see our preliminary report on the Women in Marine Mammal Science website. To see weekly highlights of the accomplishments women in marine mammal science are making in the field, follow @womeninmmsci on Twitter.

Photo by Aaron Henry for Oceans Initiative

Methods to Reduce Shipping Noise

Shipping noise is a major threat to acoustic foragers like killer whales. Killer whales and other dolphin, porpoise, and whale species, use echolocation to find their prey. When loud ships are transiting in prime foraging areas, there is a subsequent reduction in the acoustic space needed for killer whales to locate and capture their prey. We reviewed the literature and provided a comprehensive list of approaches to mitigating ship noise. Coauthors on this project used a dataset of know ship noise levels to calculate how likely these approaches are to reduce ship noise in prime foraging hotspots by 3 to 10 dB. Read more about the study in our paper, published in Marine Pollution Bulletin in 2018.

Photo by Toby Hall for Oceans Initiative.

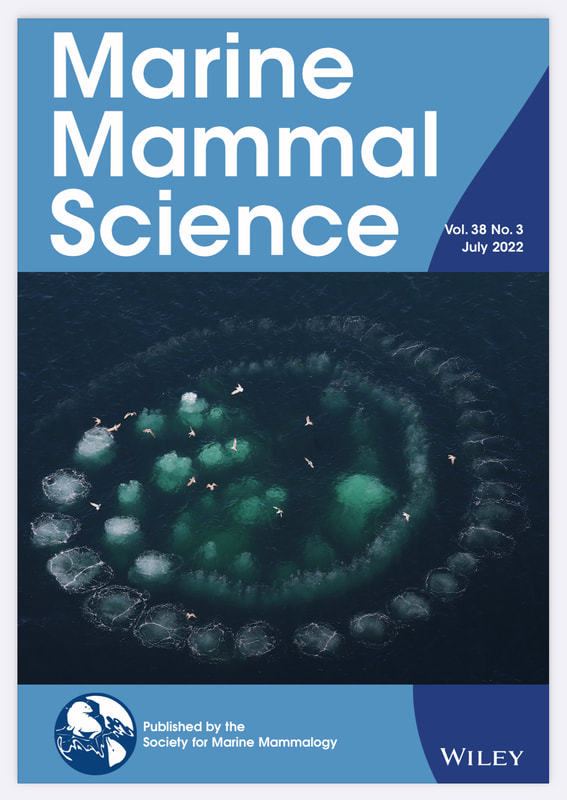

Individual Roles in Bubble-net Feeding Humpback Whales

My Masters research focused on what individual humpbacks do in group bubble-net feeding events. Bubble-net feeding is a seemingly cooperative behavior in which humpbacks work together to herd prey to the surface using bubbles expelled from their blowholes. My research compared the behaviors of humpbacks tagged performing this feeding technique in groups in three habitats-- the Gulf of Maine, Southeast Alaska, and the Antarctic Peninsula. I found that humpbacks tend to take on different roles within a feeding group to accomplish the collective goal of prey capture. Watch this video of my methods and findings. My published findings were featured as the cover article in Marine Mammal Science's July 2022 issue, and you can read it here. My entire Masters thesis, if you'd like to dive in deep, can be found here via the Oregon State University Library.