|

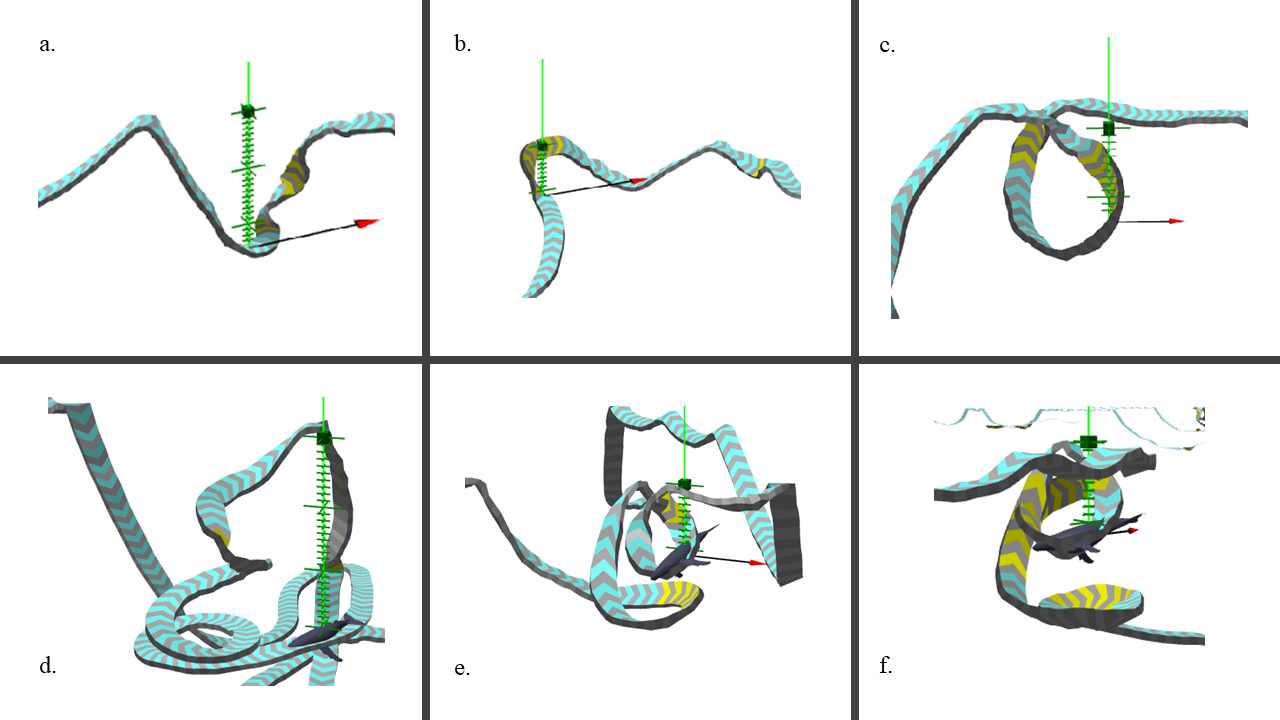

I have never been what one might call a "good eater." I have been picky since I was a little kid, avoiding major food groups and sticking instead to items covered in cheese. I was a pain in the butt to my very patient parents who just wanted me to have a balanced diet. Today, I am still a problematic dinner guest, (though less dependent on dairy,) as I adhere to a vegan diet. I would call myself what in the biology world we call a "dietary specialist." There are a lot of well known specialists, most notably the southern resident killer whale, which is mentioned all over my website, and is known for it's all raw-salmon diet. The more adaptable, "good" eaters, are known as dietary generalists. Humpback whales are very good eaters. They are flexible foragers, known to eat what small schooling fish or swarming krill are available when they are on their feeding grounds. As big whales that eat small prey, they have learned several techniques to capture their food in order to maximize their feeding efficiency. Some humpback whale populations use coordinated feeding strategies, like bubble-net feeding, to herd large schools of prey. Bubble-net feeding involves one or more members of a group diving below a school of fish and releasing bubbles through their blowhole(s), which form a wall of bubbles around the prey and help herd their prey to the surface as they dive up from underneath them, consuming them in an epic lunge at the surface. Though this behavior is seen all over the world, including Massachusetts, Alaska, Australia, and Antarctica, scientists don't know what benefit working together has for the participating whales. For my master's degree, I sought to answer this question by investigating what whales are doing underwater when they are bubble-net feeding in groups, to determine if they take on different roles. While in my masters thesis I investigated this question across three foraging grounds, the Gulf of Maine, Southeast Alaska, and the Antarctic Peninsula, I recently published my findings from the Gulf of Maine (Mastick et al. 2022). In this study, my coauthors and I tagged 26 bubble-net feeding whales. We looked at the tag data in a program called TrackPlot, which allows us to visualize the 3D movement of the whales underwater. We then assessed what differences there were in dive patterns between groups of various sizes. We found that whales participating in bubble-net dives adopted one of six dive strategies (shown above in order of increasing complexity). Dives (e) and (f) were more complicated dives, and were usually used in small groups. Dive (d), the upward spiral, was malleable (it could have different numbers of rotations,) and it was used across all group sizes. We looked at whether these dive strategies changed based on the number of whales in the group. There was no differences in the strategies based on group size except when whales used an upward spiral strategy. The upward spiral (d) technique changed based on how many whales were feeding together, suggesting that whales needed to maneuver less, and potentially work less, to effectively herd the prey to the surface. This finding shows that there may be a benefit to working together to feed -- in some situations, whales that work in a group have to do less work. Why isn't this the case across all diving strategies? Think of it like a group project in school: whether or not the work load per member is reduced really depends on the behaviors of the group members. When all group members divide up the task easily (in this case, doing upward spiral dives), the project (feeding) is done with less work required of each member. When one group member is a bit controlling and takes over (doing the more complicated dive strategies), they may end up doing more work than other participants, leading to an uneven distribution of work. If you would like to learn more about this project, you can read the article HERE. If you would like to watch a presentation on this research, watch below!

0 Comments

In May 2020, I gave a virtual talk at Town Hall Seattle through Engage Science at the University of Washington. This presentation was the culmination of three months of science communication training. In it, I cover my research on parasites in killer whales and why they're important for whale conservation. To see for yourself, watch the video below! It is appropriate for a general audience, and serves as an excellent introduction to my work. My presentation runs from 22:20-41:40. Photo from the Center for Whale Research. One of the Conservation Canines doing his job finding southern resident killer whale scat. Every time I go to the Seattle Tacoma airport, I play a game that distracts me from my travel anxiety: I Spy a dog. Ten years ago I didn’t play this game— a dog at an airport was a rare sight— but nowadays a trip to SeaTac is not complete without seeing a service dog walking with its owner, a therapy dog on someone’s lap, and a security dog sniffing luggage of travelers.

Dogs have always had jobs. They were bred for jobs, and only recently did their job transition from things like “bird dog” and “herding dog” to full time companions. Some dogs have taken this career change in stride. In Seattle, it’s rare to go to a brewery and not find a chill pup laying by its owner, just happy to be there and receive pets and attention. Other dogs still have jobs, like those I see at the airport. Therapy dogs keep their owners steady in times of stress, and airport security dogs are trained to detect weapons and narcotics. There are those dogs, however, don’t conform to a standard domestic life, and aren’t well suited for more restrictive jobs that require calm demeanors. These dogs have energy that needs an outlet most owners can’t provide on a daily basis. They want to move constantly and obsessively. A lot of the time these dogs end up in shelters, being too much for their owners to handle. But what they really need is a career change. Due to their resilience, unbounded energy, and strong noses, dogs have made invaluable helpers in all sorts of conservation studies. They’re becoming a popular tool for researchers, with several organizations popping up around the world that train dogs for conservation research. One organization, Working Dogs for Conservation, looks specifically for “bad” or “crazy” dogs in shelters, and trains them to jobs like detecting dangerous invasive species, sniffing out illegal animal contraband to reduce poaching of endangered species, and even detecting diseases in livestock. In Seattle, Dr. Sam Wasser (Center for Conservation Biology, University of Washington), and dog training expert Barbara Davenport (PackLeader Detection Dogs) founded Conservation Canines. They train dogs to sniff out the poop, or scat, of endangered species over large landscapes. Their ideal detection dog “is intensely focused and has an insatiable urge to play”— and they will go to great lengths to play. These dogs spend their days hiking in search for scat, and when they find a sample, they get rewarded with a play session and their favorite toy. The scat samples they detect are then analyzed in the laboratory, where researchers can extract genetic, diet, chemical, and hormonal data from the poop to learn a lot about the species. Conservation Canines have even taken their work to the sea, training dogs to detect endangered southern resident killer whale poop. That’s right, they bring their dogs on boats, where they can sniff out orca poop over great distances in the ocean. These samples are used by all sorts of research working to conserve this iconic orca population, including my own research on parasite infections in orcas— studies that would be near impossible without the help of a specially trained dog leading the way to the samples. The unifying feature of these organizations is that they see the potential in rescue dogs and provide them with a new life where they get to go to a fulfilling job for the payout of playtime. I have heard the phrase “there are no bad dogs, just bad owners” in the past, but maybe replacing “owners” with “jobs” would be more appropriate as these former misfits become the heroes of endangered species conservation. |

AuthorHi I'm Natalie. I'm a parasite ecologist, marine mammal researcher, and science communicator. Follow along :) Archives

March 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed